Failed Policies, Forfeited Futures: Revisiting a National Scorecard on Juvenile Records (2020)

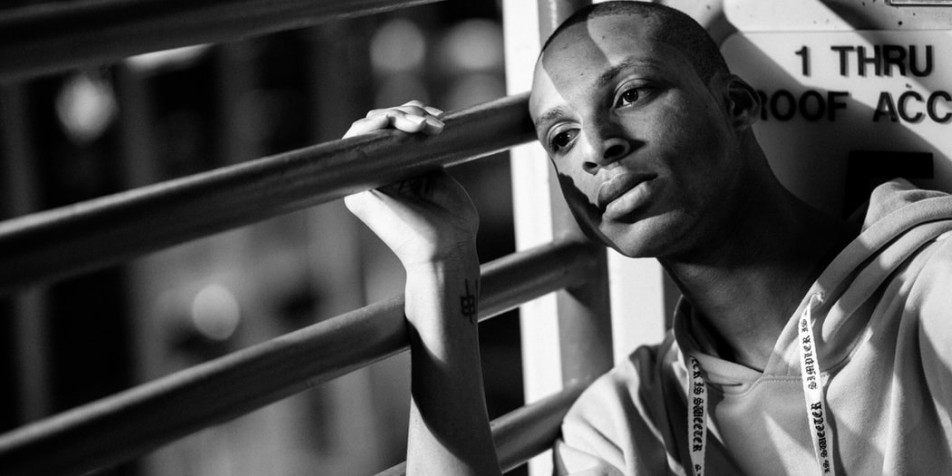

In 2014, Juvenile Law Center published the first-ever comprehensive evaluation of each state’s juvenile record confidentiality and expungement laws against our standard for best practices. The results of that study demonstrated that over 50% of the country fails to adequately protect juvenile records, leading to missed opportunities for youth who exit the juvenile justice system. Six years later, Juvenile Law Center issues this 2020 juvenile record Scorecard report, which shows some reform, but still widespread deficiencies in the legal protections necessary to keep juvenile records secured. When juvenile record information is readily available to both private and public sectors, and can be used to exclude youth from opportunities, the result of youthful actions is lifelong harm and the impact is felt greatest by Black and Brown youth.

The Evolution of Juvenile Justice and the Use of Records

Children make mistakes, and in the process they can cause harm to others and to themselves. But these mistakes are more a condition of childhood than reflective of some incorrigible delinquency or deviancy. Modern science confirms that children’s brains are not fully developed until they reach their mid-twenties. Until a child’s brain has fully matured, the child is likely to exhibit more impulsive behavior and an inability to assess and act on risks; be influenced by peer pressure and easily manipulated; but also have the capacity to reform and rehabilitate their behavior as they grow into adulthood. While the science is relatively new, the wisdom is old. Kids can and do learn from their mistakes and do better. And we are counting on their ability to continue to do so.

The juvenile justice system was founded on this principle—that young people are capable of reform and therefore the system must serve the best interests of the child with a focus on rehabilitation and the goal of ensuring that each child has an opportunity for a productive future. For rehabilitation to be truly effective and every opportunity available, it was widely understood that juvenile system involvement should be treated as confidential and that all records should be eradicated so children can start from a clean slate at the age of majority. It was tacitly understood, and today is thoroughly backed by research, that public knowledge of a child’s worst mistakes frustrates the objective of rehabilitation by limiting the child’s ability to pursue personal and professional goals. Today we know that access to juvenile record information has devastating collateral consequences for kids, leading to the denial of secondary education, housing, gainful employment, military service, and certain government benefits. Rather than doing more to keep such information closed to public scrutiny, however, states have found ways to justify providing agencies and actors more access than ever before. Meanwhile with the aid of technology, interested parties can often find ways to identify whether and what a youth has in their record, a problem that clearly frustrates the purpose of rehabilitation.

The resulting impact on Black and Brown youth is severe. While 95% of youth arrests are for nonviolent offenses, Black and Brown youth are 4.6 times more likely to be incarcerated for a nonviolent offense than White youth. This disparity not only reflects the systemic racism of a justice system that treats them with a presumption of dangerousness, but perpetuates that racism by stamping them by their sentencing record, with a presumption that would allow for the kind of discrimination our Constitution no longer permits for skin color alone. In fact, a 2003 study found that the effect of a criminal record is 40% greater for Black Americans than it is for White Americans. When states fail to protect juvenile records either by granting broad access or by making expungement and sealing costly and inaccessible, either by law or procedure, the disproportionate impact on Black and Brown youth compounds the systems of discrimination in our education, employment, and housing systems.

The 2014 Scorecard

In order to push states to provide greater protection for juvenile record information, in 2014, Juvenile Law Center undertook an extensive national review of state laws on the confidentiality and expungement of juvenile records. That work culminated in the publication of Failed Policies, Forfeited Futures: A Nationwide Scorecard on Juvenile Records, containing an interactive scorecard rating and ranking states against a set of Core Principles developed from our research and analysis.

States were graded from 1 to 5 stars, with 5 being the highest score. States were then ranked by their overall scores, as well as by scores specific to questions around the confidentiality of records and scores specific to the availability of sealing and/or expungement of records.

The overall average score of all 50 states plus the District of Columbia was 3 stars. No state received 5 stars overall. Only eight states received 4 stars. 28 states received 3 stars; 14 states received 2 stars; and Idaho was the only state to receive 1 star.

In the confidentiality category, six states received a 5 (Rhode Island, New York, Vermont, Wyoming, Nebraska, and Ohio). At the other end of the spectrum twelve states received only 1 star.

For sealing and expungement most scores again huddled around the middle, with roughly an equal number of 2’s, 3’s and 4’s, no 5’s or 1’s.

In the wake of the scorecard publication, increased advocacy helped some states and municipalities improve or change their juvenile records’ laws, but there remains ample room for improvement in states across the country.

Scorecard 2.0: The 2020 Update

Over the last year, with the help of our partners at Troutman Pepper, Juvenile Law Center revisited the laws in every state and the District of Columbia to reevaluate how well the country protects confidentiality and expungement of juvenile records. We measured each state’s laws against a set of core principles for optimal record protection:

■ Youths’ law enforcement and court records are not widely available and are never available online

■ Sealed records are completely closed to the general public

■ Expungement means that records are electronically deleted and physically destroyed

■ At least one designated entity or individual is responsible for informing youth about the availability of sealing or expungement, eligibility criteria, and how the process works

■ Records of any offense may be eligible for expungement

■ Youth are eligible for expungement at the time their cases are closed

■ There are no costs or fees associated with the expungement process

■ The sealing and expunging of records are automatic—i.e., youth need not do anything to initiate the process and youth are notified when the process is completed

■ If sealing or expungement is not automatic, the process for obtaining expungement includes youth-friendly forms and is simple enough for youth to complete without the assistance of an attorney

■ If sealing or expungement requires a process, youth have access to a hearing and counsel to represent them at such hearing.

■ Sanctions are imposed on individuals and agencies that unlawfully share confidential or expunged juvenile record information or fail to comply with expungement orders

■ Juvenile delinquency adjudications should not be considered the same as criminal convictions as a matter of law, nor should they be used as evidence in any subsequent delinquency or criminal proceeding

■ The public should never have access to juvenile courtrooms during a juvenile proceeding

The scoring was modified from 2014, with some new questions included to try to better capture and differentiate the full range of approaches and practices employed across all 50 states and the District of Columbia with respect to the protection of juvenile record information. Some of those changes include:

■ Looking for the first time at whether juvenile court proceedings are open to the public

■ Whether delinquency adjudications can be used against youth in future proceedings

■ Separating the scoring of confidentiality protections for court and law enforcement records from the individual exceptions to confidentiality, with a greater range of possible scores reflecting different levels and degrees of access and exposure

Despite the modified scoring, the general breakdown of scores remained largely unchanged, reflecting little overall improvement in providing youth confidentiality and a clean slate for their early system contacts.

Overall, the national average was 47% (46% in 2014), with over 60% of states receiving 3 stars. There were no states that received a 5-star rating, nor any states that received only 1 star. California tops the overall rankings with a score of 70% (in 2014 the #1 spot went to New Mexico at 74%), while Arizona (at 24%) takes over the bottom position from Idaho, which still remains in the bottom 20% of all states. The state with the most improvement in scores appears to be Oregon, which in 2014 was below the national average at 43% and now is one of only seven states to receive 4 stars (at 60%).

Confidentiality scores continue to reflect the greatest variance among states. Rhode Island is still at the top, with the only 5-star score and a perfect 100% score. Aligned with our core principles, states can use Rhode Island’s law as a model. Two states received 1 star with Idaho still at the bottom at 12%. With respect to sealing and expungement practices, California, Oregon and Oklahoma were at the top (70%, 68%, and 67% respectively) while Arizona, Utah and South Dakota were at the bottom (with 27%, 27%, and 25% respectively).

Conclusion

Juvenile Law Center’s 2020 assessment makes clear that there remains a need for states to reform their juvenile record laws. There are a number of states exhibiting good to fair to good practices in confidentiality or expungement, but no state exhibits high standards of practice in both. Youth, and in particular, Black and Brown youth, would be better served if states took action to reform their current laws and practices. In the last six years, there has not been significant movement from the original scoring, suggesting not nearly enough states are taking this issue seriously despite greater research into the collateral consequences of youth records and greater awareness and advocacy around the systemic racism reflected and perpetuated by these laws.

To ensure the juvenile justice system serves its intended purpose of giving all youth who come in contact with it the greatest opportunity for success, protecting juvenile record information from access and use in any other setting is of paramount importance. To that end Juvenile Law Center recommends that: (1) policymakers, including legislators, lobbyists, interest groups, and governors of all states undertake immediate evaluations of their juvenile records policies and, where gaps are identified, put forth legislative proposals to close them; (2) legislators and municipalities enact—and employers should pledge to abide by— proposals to limit the barriers a juvenile record imposes in obtaining education, employment, housing, and other benefits; (3) states pass laws requiring that juvenile records and juvenile record information be sealed until a case is closed or the youth reaches the age of majority, at which time (4) all juvenile records should be automatically expunged.