A Demand for Humanity: When They See Us and Police Coercion of Black Youth with Language and Learning Challenges

This blog is part of a series Juvenile Law Center is presenting related to Ava Duvernay's newly released Netflix miniseries When They See Us about the Central Park Five. Follow the conversation online with #WhenTheySeeUs and be sure to watch. Take action here.

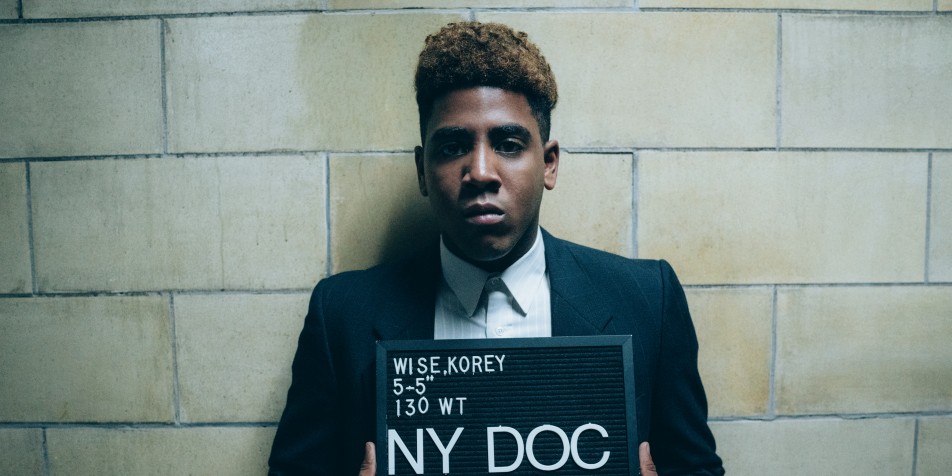

In Ava DuVernay’s When They See Us Netflix miniseries, 16-year-old Korey Wise, played brilliantly by Jharrel Jerome, shows us the extraordinary risks of police abuse facing youth who are young, Black, and living with language and learning challenges – and also the humanity and heroism of an individual standing by his friend, fighting for his family, and speaking his truth in the face of a horrifying system.

As Tambay Obenson has described, the Central Park Five, or as DuVernay thoughtfully renamed them, the “Exonerated Five” were convicted in a city "blinded by fear and equally, weighed with racial conflict." The film highlights the racial animus – from the barely coded language about teenage “animals” out “wilding” in the park, to the explicit call from Donald Trump to reinvoke the death penalty. Race alone made the Exonerated Five vulnerable to discrimination and police abuse. That they were just children, from ages 14 to 16, put them at even greater risk.

Korey’s story reveals – in heartbreaking detail – yet another problem: youth, especially Black and Brown youth, with language and learning challenges are uniquely vulnerable to coercive police practices. Duvernay brilliantly illustrates Korey’s educational and communication challenges. Korey’s girlfriend tells him “if you would come to school more often, then we would get to spend more time together,” giving us the first hint that his schooling is not going smoothly.

During his police interrogation, we watch Korey’s difficulty hearing and responding to the questions asked of him, providing another indication he may be experiencing communication challenges. Later during the trial, when the prosecutor shows him his signed statement and asks him to read it, we learn that detectives wrote the confession and Korey has difficulty reading the words. “I can’t read well,” he says. “I said I can’t read very well.” When the prosecutor then changes tactics and asks about Korey’s history of truancy, he explains that he missed school because he was threatened. But the education system’s failure to protect him, or adequately teach him, is not at issue. Instead, the prosecution hammers home Korey’s school absences to paint a picture of his guilt.

Korey aptly asks, “What does that have to do with my case?” and comments that he doesn’t want to answer questions because “answering questions is what got me here in the first place.” And he’s right. We watch, during the interrogation, as Korey falsely admits, on video, “This is my first rape. This is my first experience. This will be my last,” believing that his remorse will allow him to go home. We also see Korey forced into a confession by police who hit him and slammed him against the wall. But even absent physical violence, research explains that adolescents have trouble with the cognitive, emotional, and communication skills required in police interrogations, and youth with language and learning challenges are at an even greater risk because they may have trouble with vocabulary, comprehension, verbal expression, recall, and a host of other skills required in the interaction.

The U.S Supreme Court has held that age matters in interrogations. Obviously, when the jury fails to believe that Korey confessed because of abuse, the law is failing its goals. But more broadly the legal framework is also insufficient to protect him, or thousands of other children in his position, from coercion based on their race or their communication and educational challenges. The Court has not established a clear standard for how to address cognitive, rather than chronological age, nor have they fully recognized the importance of cognitive and communication skills in interrogations. While a few state courts have recognized that how an individual responds to police will be influenced by their race because racial profiling is so prevalent, the U.S. Supreme Court has not recognized that race matters in interrogations. And it certainly hasn’t recognized how an individual’s layers of identity and knowledge work together. Language and learning challenges are not specific to any one race, ethnicity, or gender. However, the history of structural racism resulting in racial disparities in policing and in the courts mean that Black youth with language and learning challenges are uniquely at risk of unfair prosecution.

More deeply, we see a system willing to ignore and dehumanize Korey, who is anything but one-dimensional. We see his loyalty, his generosity, his love. We know that Korey went to the police station just to support Yusef. “He’s my friend,” Korey explains. We see him in the jail visiting room asking his mother how he can help her. “Anything I could do? Anything?” he asks. We see his loving bond with his sister, and his devastation at learning that she has died while he was locked up.

When They See Us poses so many vital questions – how do we create a legal system that treats youth of all races fairly? What does it mean to ensure due process for a teenager? How do we best address a child’s unique needs and language and learning challenges? Can a teenager, especially one with language and learning challenges, ever validly confess without an attorney present? But it’s worth noting that our solutions can’t be one-size-fits all. By sharing the complexity of Korey’s story, Duvernay reminds us that “seeing” individuals in the system requires us – and the legal system – to delve deeper and consider a person’s individual characteristics, their history, and their humanity.