Mandatory Minimums, Maximum Consequences

Image credit: https://www.flickr.com/photos/donshall/1858459388/

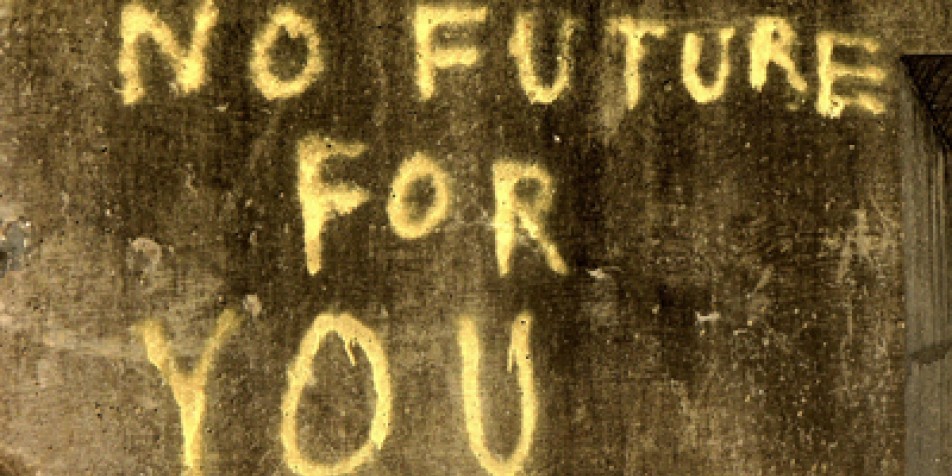

Over twenty years ago, academics and lawmakers promoted the idea that some children were “so impulsive, so remorseless” that they would “kill, rape, maim, without giving it a second thought.” The theory behind these “juvenile superpredators” has since been entirely disavowed, but the “tough on crime” laws enacted in response, which led to harsh mandatory sentences imposed on youth, still impact individuals who remain behind bars today.

Recently, United States Attorney General Jeff Sessions reversed an Obama administration directive that gave federal prosecutors and judges flexibility to sentence offenders below statutorily mandated minimums. In Pennsylvania, a similar bill has been referred to the state Senate Judiciary Committee that would revitalize mandatory minimum sentences in the state. Mandatory minimum sentences have not been enforced in Pennsylvania since 2015 per a state supreme court ruling that the process used to impose the sentences were unconstitutional.

The revival of strong mandatory sentencing schemes matches the “tough on crime” approach touted by the Trump administration. While mandatory minimums negatively impact all individuals involved in the criminal justice system, youth particularly face long-term consequences. The imposition of mandatory minimums exacerbates the harms that youth face in the adult criminal justice system and forces children to grow up within a system that lacks age-appropriate education and treatment to address their rehabilitative potential.

Juvenile Law Center recently advocated for youth when the state of Washington grappled with the issue of mandatory minimums imposed on children tried as adults. On Halloween night, 2012, friends Zyion Houston-Sconiers, 17-years-old, and Treson Roberts, 16-years-old, were arrested for stealing candy and cell phones from trick or treaters. Both boys were charged with multiple counts of robbery, other felonies, and - because Zyion was armed with a revolver- a number of firearm enhancements.

Due to a Washington statute requiring automatic transfer to adult court for juveniles charged with robbery, the boys were tried and convicted in the adult criminal system. Zyion faced a sentence range of 42-45 years, 31 of them required by mandatory firearm enhancements. Treson was facing 37-40 years. At sentencing, the State of Washington recognized the “perhaps excessive” sentence length required for the boys, requesting a departure from the mandatory requirement. The trial judge complied, noting he “wished he could have done more to reduce their sentences,” but Washington’s mandatory sentencing laws prevented him from doing so. As a result, Zyion was sentenced to 31 years and Treson was sentenced to 26 years, both without an opportunity for parole. On appeal, the Washington Supreme Court affirmed the convictions of Zyion and Treson, but effectively forbid mandatory minimum sentencing for juveniles by holding that the trial court must have “full discretion to depart from the sentencing guidelines and any otherwise mandatory sentence enhancements,” and must take the defendant’s youth into consideration during sentencing.

In 2014, the Iowa Supreme Court delivered a similar ruling holding mandatory minimum sentences unconstitutional as applied to juvenile offenders, finding such schemes "cannot satisfy the standards of decency and fairness embedded in article I, section 17 of the Iowa Constitution."

While the Washington and Iowa Supreme Court decisions were considered major victories, they do not reach beyond their states. Many other states have enacted or are enacting mandatory sentencing laws that will affect the estimated 200,000 youth tried and sentenced as adults each year. When children convicted in the adult system are subjected to mandatory sentences, the court cannot consider whether a child may be reformed through rehabilitative treatment or if their age may have played a part in their offense. Instead, courts are bound by the sentences mandated by the law. This practice undermines the determination that “children cannot be viewed simply as miniature adults.” The United States Supreme Court has explicitly recognized that children have “diminished culpability and greater prospects for reform” and are therefore “less deserving of the most severe punishments.”

When sentencing youth, it is important to make individualized determinations of culpability that not only look to the age of a minor, but the “background and mental and emotional development of a youthful defendant.” The Court has consistently recognized that youth possess levels of maturity, decision-making ability, culpability, and capacity for change and growth that differs substantially from adults. Automatic sentencing denies these and other individual characteristics of youth from being taken into account and can have long-lasting detrimental effects on children.

Subjecting youth to prosecution in the adult system in the first place deprives youth of the rehabilitative nature of the juvenile justice system and its programs, classes and activities specific to the needs of youth. Compared to youth in the juvenile system, youth in the adult system are five times more likely to be sexually assaulted during their incarceration, and two times more likely to be assaulted with a weapon. These youth are also more likely to be psychologically affected by the conditions of confinement and more likely to commit suicide. Research has shown that youth who have served sentences in the adult system reoffend more quickly and violently after release than those who served their time in the juvenile system. Each of these consequences are further exasperated by mandatory minimums that subject youth to lengthy prison stays that far surpass their culpability.

The juvenile system was modeled on the belief that children should be rehabilitated rather than punished. This ideology is undermined by the enforcement of mandatory minimum sentences for youth offenders. The juvenile “superpredator” misconception is widely recognized to have caused immeasurable harm to families and communities. So, too, should be the laws that emerged from this fallacy. Mandatory minimum sentences are harmful for youth. We should move away from these schemes rather than revitalizing them into present day law.