Lessons from "Kids for Cash," Part 9: The Focus of the Juvenile Justice System is Rehabilitation, Not Incarceration

This is the ninth blog post in our Lessons from "Kids for Cash" blog series, which explores some of the critical issues facing youth today that were brought to light by the "kids-for-cash" scandal and are depicted in the new film "Kids for Cash." "Kids for Cash" is currently playing in theaters across the country.

Our nation’s first juvenile court was established in Illinois in 1899. The court process at the time was informal, often nothing more than a conversation between the youth and the judge. Youth did not have lawyers—a child’s constitutional right to counsel in delinquency proceedings was not recognized. This right did not come until 1967, when the U.S. Supreme Court issued its landmark ruling in In re Gault that children were entitled to many of the same rights as adults who committed crimes.

In establishing a juvenile court system, early juvenile justice experts in Illinois recognized that it was not a good idea to put kids in jail with adults. They instead created a probation system and used a separate service-delivery system to provide kids with supervision, guidance, and education: services that kept them safe and prepared them for success.

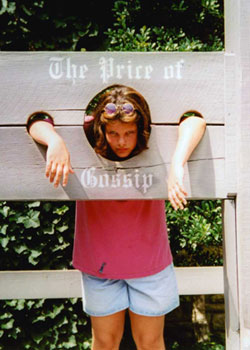

Former Luzerne County juvenile court judge Mark Ciavarella deemed kids who committed "crimes" like unknowingly purchasing a stolen scooter or creating a fake MySpace page (as Hillary Transue, pictured above, did) as "children who need help."

Former Luzerne County juvenile court judge Mark Ciavarella deemed kids who committed "crimes" like unknowingly purchasing a stolen scooter or creating a fake MySpace page (as Hillary Transue, pictured above, did) as "children who need help."This juvenile court system served as a model for the rest of the states and the District of Columbia, which quickly followed Illinois’ lead and established their own juvenile courts.

While the juvenile justice system has changed and evolved over time, its primary goal—to rehabilitate children who need help—has not changed. Yet in schools, communities, and courtrooms across the nation, we continue to lose focus of that goal by widening the net of “children who need help” and by relying on inappropriate, overly punitive methods—rather than rehabilitative ones—to hold children accountable for their actions.

Nothing illustrates the disastrous consequences of those actions more clearly than the Luzerne County “kids-for-cash” scandal. Former juvenile court judge Mark Ciavarella deemed kids who committed “crimes” like unknowingly purchasing a stolen scooter or creating a fake MySpace page as “children who need help.” Often with no attorneys present in the courtrooms to protest, Ciavarella sent those kids away to out-of-home residential facilities, like wilderness camps and secure juvenile facilities: harsh punishments that did not fit the crime, help the kids, or protect the public. On the contrary, these children were severely traumatized, had their educations derailed, and their childhoods stolen. Most still struggle to regain any semblance of normalcy and will never fully recover from the experience. Sadly, school administrators, law enforcement officers, prosecutors and judges all over this nation are following this same philosophy.

In fact, 95% of youth arrests each year are for non-violent crimes or probation violations. Removing these children from their homes and sending them to secure facilities and camps does not fit the nature of the juvenile justice system: it does nothing to improve the safety of the public since there was never any risk in the first place, and it does nothing to rehabilitate children since they were not in need of rehabilitation in the first place. The only result: millions of traumatized children and billions of wasted taxpayer dollars.

As we know, kids are different from adults: they are less mature, and more likely to act carelessly and impulsively. It is common sense—and every parent recognizes that teenagers often don’t think before they act. Adolescents make mistakes; it is part of the normal maturation process. Severely punishing kids for what is normative behavior and in a way that is disproportionate to the act only serves to damage children, set them up for failure, and permanently damage their belief in justice and fairness.

How Can We Solve This Problem?

1. Limit involvement in the juvenile justice system to kids who have committed only the most serious crimes.

Children who have committed serious crimes are clearly in need of supervision, help, and rehabilitation—services that the juvenile justice system was founded to provide. These children can benefit from system involvement, and because the system can help those children learn how to positively contribute to society, the public benefits as well.

2. Stop subjecting kids to overly harsh sentences that do not take into account their immaturity and capacity for rehabilitation.

When juvenile crime peaked in the late 1980s and early 1990s, states adopted “get-tough” policies for crime, and enacted policies to prosecute more youth in adult criminal court, rather than juvenile court. Many of these new state laws exposed youth to the dangers and potential abuses attributed to incarceration with adult offenders, much like they’d experienced before the creation of the original juvenile court more than a century ago.

|

We must make sure that when dealing with youth offenders, our focus is on rehabilitation, not incarceration. Kids must be held accountable, but society will ultimately benefit most when this is done in developmentally appropriate ways. |

Despite the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2012 ruling in Miller v. Alabama banning mandatory life without parole sentences for children, many offenders are still serving life sentences in prison for crimes they committed as kids. These youthful offenders have no chance of ever being released—despite the assertion from the American Medical Association and the American Psychological Association that youth is a “transient characteristic” and that kids have a greater capacity than adults for rehabilitation. We must make sure that when dealing with youth offenders, our focus is on rehabilitation, not incarceration. Kids must be held accountable, but society will ultimately benefit most when this is done in developmentally appropriate ways.

3. Kids who commit non-violent crimes should be kept out of the system and connected instead to services in their community.

Youth who have been “adjudicated delinquent” (found guilty) will have juvenile records and may face serious long-term consequences as a result. Additionally, research shows that sending kids to out-of-home placements actually increases the chance that they’ll reoffend. It makes sense, both for children’s futures and for the taxpayer’s wallet, to keep those who have not committed serious crimes out of the system.

Juvenile Law Center advocates for “diverting” youth into programs or treatments that can more appropriately address their needs. Examples of community-based diversion programs include youth courts, evidence-based practices for youth and families, restorative practices (like SaferSanerSchools) and Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative. Judges can also choose to move youth offenders into the child welfare system, rather than the juvenile justice system, so that they can still be supervised by the court and can access behavioral health services without having to leave their homes or get saddled with a juvenile record.

If children are the future of this country, we all need to take a hard look at how we are treating our youth and do something to change it, starting in our own backyards.