Redefining Justice One Year After Miller v. Alabama

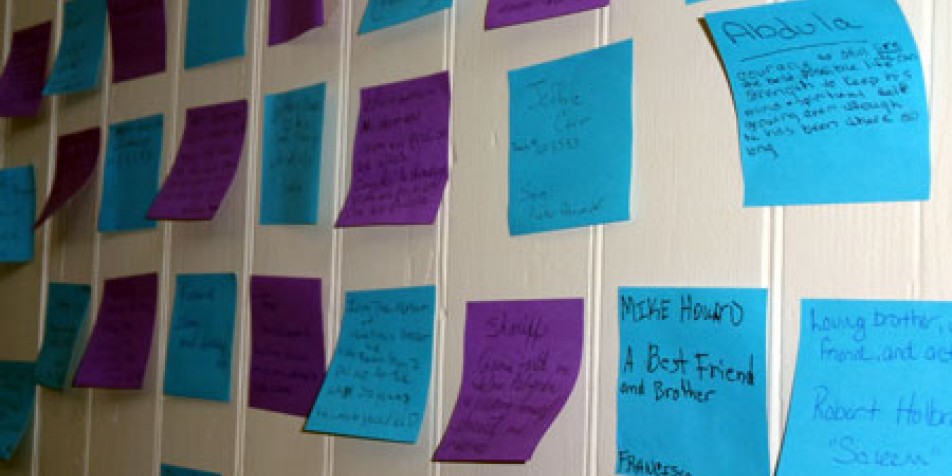

Above: Sticky notes posted on the wall during a recent Pennsylvania Coalition for the Fair Sentencing of Youth (PACFSY) gathering honored some of the roughly 500 inmates currently serving juvenile life without parole sentences in Pennsylvania. The state has more inmates serving these sentences than anywhere else in the world.

One year ago, in Miller v. Alabama, the U.S. Supreme Court declared that mandatory life without parole sentences for youth were unconstitutional. The Court ruled that mandatory sentencing of children restricts a judge's ability to consider the child's mitigating circumstances, maturity, or ability to be rehabilitated. The Court noted that juvenile life without parole (JLWOP) sentences should be rare.

The Supreme Court did not, however, address several related issues:

Retroactivity

If it became unconstitutional for states to apply mandatory JLWOP on June 25, 2012, what about the over 2,100 men and women sitting in U.S. prisons who were sentenced prior to that date? What about those whose appeals expired on June 24th? Are their constitutional rights null and void simply because their sentences were handed down prior to that date? The Constitution was meant to provide justice for all—not justice according to date of application. An unconstitutional sentence cannot be applied to any defendant. Yet some prosecutors continue to claim that Miller does not apply retroactively and that the now-unconstitutional sentences cannot be reviewed.

Life Without Parole

|

My brother was incarcerated in 1969. I love him and miss him dearly. He's a very strong and caring man. He's never given up since he's been away—41 years! He has been giving me hope through all of his letters, actually helping me throughout my life through letters of hope. Brother of a juvenile lifer |

Many states seek to circumvent the spirit and letter of the Miller decision by substituting lengthy mandatory minimum sentences for life without parole. Almost immediately after Miller, one governor went so far as to say "he disagreed with the Supreme Court's decision" and would commute all of the affected individuals' sentences, instead requiring a mandatory mininum of 60 years in prison. Legislatures have struggled with how to respond to Miller. Courts continue to sentence youth to terms that are the equivalent of life sentences. The Supreme Court has yet to rule on the constitutionality of such sentences.

As Juvenile Law Center works to ensure that Miller is fully implemented, we also recognize the totality of the tragedy that occurs when children participate in homicides—it is a tragedy that creates a devastating ripple effect. Victims' families suffer a permanent loss. We share their grief. The family of the child who committed the act also loses a loved one—not in the same way, but everyone involved experiences the death of hopes and dreams.

Sharletta's Story

The anniversary of Miller also provides an opportunity to reflect upon the potential for healing and reconciliation. Sharletta Evans lost her three-year-old son in a drive-by shooting in 1995. It was an incomprehensible loss that nearly consumed her. But at a recent gathering in Washington, D.C. Sharletta described the day one of the shooter's family members came to her and asked for forgiveness. She described her rage at this person who dared to make such a request. Yet the family member's act of contrition created a crack in Sharletta's long-standing anger and hurt. The crack widened. In the months that followed, she told of a growing need to get answers ... to understand, to meet with the man who was 14 years old when he shot her son and ask him, why? This past Mother's Day, this young man asked Sharletta if she would fill the role of mother in his life—and she agreed to do so.

A tribute to Sharon Wiggins hangs on the wall during her memorial service at a recent PACFSY Gathering

A tribute to Sharon Wiggins hangs on the wall during her memorial service at a recent PACFSY GatheringSharletta Evans is an extraordinary human being—one who suffered an indescribable tragedy, and yet found healing through compassion for another. According to Sharletta, "It is possible to find closure. It truly is." She understands the pain and loss both families experience and added, "Many people feel these young men don't deserve a second chance. I agree. (pause) Because most of them never had a first chance." Sharletta explained that many of those serving JLWOP were failed by society and that they are paying the price for the failures of all of us. Remarkably, Sharletta is now a vocal supporter to reform JLWOP sentencing laws and give these men and women hope for a future—and an opportunity to give back to society.

Sharon Wiggins never got that chance. She died in prison waiting for the issue of retroactivity to be decided (read about Sharon's story here). At her memorial service, the brother of another juvenile lifer described his relationship with his imprisoned brother who is also awaiting that decision. "My brother was incarcerated in 1969. I love him and miss him dearly. He's a very strong and caring man. He's never given up since he's been away—41 years! He has been giving me hope through all of his letters, actually helping me throughout my life through letters of hope." It seems that hope and healing often go hand in hand.

We must achieve a more rational, logical, compassionate response to this issue. Compounding one tragedy with another is not the answer.